Self-Improve with Conservation

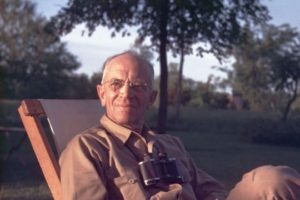

Aldo Leopold. (photo: aldoleopold.org)

At holiday time, life is a flurry of activity, followed by a period of hibernation. We busy ourselves now with buying, giving, and celebrating. Then, with the start of the New Year, we resolve to somehow do better. To lose weight, to read more, to self-improve. Perhaps we look ahead to the changes in politics and wonder what that future will hold; a time of change in social, economic, and environmental realms. In a way, the things Aldo Leopold had to say about the natural world might be a good guide in the days to come.

One of America’s earliest and most important conservationists, Leopold wrote The Sand County Almanac, a series of essays about the ties between the land and the people living with it, in 1949. He was concerned then with the endless manipulation of the land in pursuit of material objects at any cost. “Like winds and sunsets, wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them. Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free. For us of the minority, the opportunity to see geese is more important than television, and the chance to find a pasque-flower is a right as inalienable as free speech.” The Almanac contains a blend of observations about the woods and fields, but also about human beings and the tension between consumerism and conservation. As he said in the preface, “There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot. These essays are the delights and dilemmas of one who cannot.”

The Land Ethic

When Leopold was born in 1887, America’s natural resources seemed boundless. Pine forests were being cut down to make way for farms, which in turn were planted with little thought to soil conservation, nor to the animals vanishing from the region as a result of the cutting. So much of America was being dredged, cut, plowed, and drained. The thinking was that there was more than enough of every resource, and that the land was capable of limitless rejuvenation from the abuses heaped upon it by a growing nation.

According to Green Fire, a documentary about his life, Leopold’s parents made it a point to encourage young Aldo to experience the outdoors and make discoveries with a level of enthusiasm that would make today’s helicopter parent faint. His interest in the natural world grew, and he found that his family couldn’t afford his own pair of binoculars. However, his mother, a great fan of the opera, allowed him to borrow her opera glasses in order to expand his observations.

Leopold came of age during the first wave of conservation in the early 1900’s. He lived through Teddy Roosevelt as president, an avid hunter and whose love for the outdoors was reflected with the establishment of the national park system. Leopold saw what was happening to the land in the 1920’s and 30’s and was alarmed. “I came home one Christmas to find that land promoters, with the help of the (Army) Corps of Engineers, had diked and drained my boyhood hunting grounds… my home town thought the community enriched by this change. I thought it impoverished.”

Since there was no such thing as a conservation major then, Aldo Leopold went to Yale University to study forestry. After graduation, he began what would become a decades-long career with the US Forestry Service. Much of that time was spent traveling the vast expanse of the middle and southern parts of the country in order to determine what exactly was out there. It was here that he began to develop the notion that would make him perhaps most noteworthy: the land ethic. “The land ethic came as a result of understanding the interconnectedness of the land and humanity,” said Nina Leopold Bradley, Aldo’s daughter. In the early to mid-20th century, this was a novel idea. As one rancher put it, “We were out to conquer this country, not preserve it. We finally started to realize that we’re not just responsible for that species, or this one, but the whole forest.”

Reading the outdoors

The Sand County Almanac contains a segment based on the calendar year. In the December chapter, Leopold reads the woods like others read their Sunday papers; grouse, deer, and pines all reveal secrets to him that few others bother to take the time to read. Throughout, Leopold sprinkles in observations about humanity with those of nature. Through years of observation, he finds that the growth of pine trees contains a record of conditions from one year to the next. For example, he notes that drought years can be detected by layers of branches spaced closer together than in years where rainfall is plentiful. He also gives a nod to the ways in which the trees may have wisdom that mankind lacks, as he remarks on the growth during a fateful year in American history: “The 1941 growth was long in all pine; perhaps they saw the shadow of things to come, and made a special effort to show the world that pines still know where they are going, even though men do not.”

Listening to Leopold

Aldo Leopold’s work is a guide for those who would break with the imprisonment of the dark days of winter and who would be reminded that yes, life continues even in the days of chill and limited daylight. And perhaps it is a reminder of one person who saw the rampant destruction of America’s wild places and spoke up about it. “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect… Perhaps such a shift of values can be achieved by reappraising things unnatural, tame, and confined in terms of things natural, wild, and free.”

Reading a bit of Aldo Leopold might be a good way to spend the quiet moments of winter. Perhaps doing so would be a good New Year’s resolution, instead of promising to lose weight. In fact, we could well accomplish both: losing weight because we are getting outdoors, while reminding ourselves of our place in the community of life that envelops us. It may give us comfort to know that, while faced with rigorous challenges to conservation by changes in politics, there are those who still believe that protecting the wild places of the earth, whether small or large, is of highest priority. “To those devoid of imagination, a blank place on a map is a useless waste; to others it is the most valuable part.” What better way to enjoy the holidays?

A great post, Hugh! I remember reading Leopold way back in the 70s, when “ecology” and “environmentalism” were brand-new ideas. You’ve inspired me to go back and re-read the Almanac, and reconnect with that essential nature connection that drives us.

Thanks and happy new year!

Thanks so much for the comment! I remember in junior high school when I used to volunteer at a bottle recycling center long before it became required. We’ve come a long way!